Reclaiming Life After a Hemiplegic Migraine

Many illnesses are “invisible” and, in our society, the natural tendency is to insist that a person just “get on with it, deal with it.” When an illness isn’t visible, patients often put on a false face that hides what they are going through. Lying in a hospital or at home, with questions of an unknown recovery and prognosis that heighten concerns about a loss of identity, income, and social opportunities often make keeping in contact with people difficult. Well-meaning, concerned friends and family often create an exhausting environment, as their questions force the patient to endlessly recount their situation or risk alienating loved ones by telling them they don’t want to talk or have visitors.

Those who live with an invisible illness are keenly aware of how much it costs them in order to function in society. It takes effort to fight the depression and exhaustion that comes from constant health problems. It takes effort to fight through the well-meaning but annoying advice offered by friends, family, and new acquaintances as they offer up remedies based on what they heard, or what they read. Sometimes, it even takes effort to just put one foot in front of the other on any given day, literally and figuratively. It takes effort just to keep going.

Those that know Katie today know that there will be days when she isn’t going to be out in public. There are days where meetings and plans will get rescheduled or canceled. The reason for this can be seen on her left wrist on the days she wears her brace. It’s the one remaining visible reminder of Katie’s story of survival and perseverance. Her story illuminates the struggle that people go through when those around them just don’t get it. It’s also a darkly honest and messy story about loss, recovery, doubt, and triumph.

What many people did not know is that, from a very early age, Katie was living with an invisible illness. “I had migraines for 20 years. Since I was little, about three years old, my mom says when I was that young, I would say my head hurts and [then] vomit. I would have the aura, the whole traditional thing. You have this invisible illness,” she says quietly. “No one really believes that you are sick. This is what I am used to.” This seemed like something she would just have to live with as no cure could be found. It was hard for people in her life to understand what she was going through and could also be frustrating when she needed help.

The migraines did not stop her from living her life though. Upon graduating from college, Katie was determined to put academics behind her and focus on marketing. She says, “I love people, I love storytelling. I always loved learning and knowing people’s stories. I was always drawn to marketing because it was telling people’s stories in some sort of capacity. I lived in Toronto for a bit and worked at a couple of ad agencies and then I came home where I got a job here. Eventually, I went out on my own.”

Katie has the fierceness that an entrepreneur needs. She thought, “I’m doing this and I have no backup plan so it better work!” It’s just part of her personality, her way of thinking. When her mind is made up it’s like, “this is going to work for me regardless of what anyone tells me.” And it wasn’t easy. “There’s a lot of naysayers out there that told me it wasn’t going to happen. They would bring to my attention competitors. But I think it almost helps that they did that, because it lit more of a fire in me. Either I cut them out of my life because they weren’t supportive or I was just like ‘I’m going to prove you wrong!’”

Katie did prove them wrong. She built up a client base and had a nice office near the centre of the small city she lived in. She was involved in charity and performed volunteer work in addition to growing her business. To cap it off, she was about to marry Sid, her firefighter fiance. But this was all just a prelude to the next chapter of her life which would prove to be a crushing test of her spirit and her will. Those migraines she managed to live with were about to give her the fight of her life.

Katie would soon find herself waking up in a hospital bed, with paralysis spreading down the left side of her body.

The Hemiplegic Migraine Strikes

“For about a week before this happened, I was getting weakness in my left hand,” and to Katie this was odd. “I always have right side deficits, but I was having left side deficits so it was kind of out of the ordinary, but I was like, ‘OK, there is a lot of stress going on.” She was planning a large wedding, running her business, and also planning a surprise birthday party.

A few days later she found herself with Sid at a local fundraiser. “There was a Big Bike Event for Heart and Stroke, and back then I was on the board for our local [Business Improvement Area Council] and I had to do that. All of a sudden, my hand was not working at all. And so my fiance said ‘you need to go to the ER,’ because he was noticing signs that were not well.” But she thought to herself, “I’ll just do this Big Bike run first, and then I’ll go to the ER”. Later, at the ER her symptoms continued to worsen. “I’m sitting in the ER and my foot goes out, and I can’t use my foot. It’s all happening all at once.”

The confusing part was that her constant headache was not much worse than usual. Doctors ask patients to rate pain on a scale of 1 to 10. Katie explains, “Every day of my life I stood on a 4. I always have a headache. 10 means I have to go to the ER, I need something to kill this pain. That day I was sitting on a 6, which is not abnormal. I’ll just take a Tylenol and hope it goes away a little bit.”

This time, something seemed different. “That’s why it was so alarming. I had these deficits on my left side and I had a little bit of a headache and then I was losing my speech capacity, too. I was slurring my speech.” Sid, her fiance, feared she was having a stroke.

Over the next few hours, her local hospital performed a CT scan and administered the prescribed cocktail of medications. When the scans came back clear, the doctor thought she should still have an MRI the next day, so they admitted her overnight. Initially, her symptoms seemed to be resolving, but in the morning things had become worse. Katie recalls, “When I woke up the next morning, [these symptoms] got severely worse. I lost everything on my left side and I couldn’t talk, pretty much, at all.” Stumped, the decision was made to send her to a different hospital in London, Ontario which was larger and had a neurologist on staff. It was felt that with London’s additional resources and specialists, an answer might be found.

In London, the tests started all over again. “At first when you get there you go to the ER. It’s not like the head doctor looks at you. He sends his most junior resident.” This resident will determine if the specialist will take on her case. Katie continues, “So, he lifts up my arm and it falls and hits me in the head and smacks my glasses–knocks my glasses off! He looks at me and goes, ‘oh.’” Through slurred and muddy words, Katie managed to ask her mom “‘why did he do that?’ ‘Because,’ she replied, ‘if you were doing this for attention your reflexes would have automatically kicked in and you would have not hit yourself in your face, but because you can’t control it at all, it’s obviously something more.’”

Katie was put on the neurologist’s caseload, but she did not see much of him. Since she was in a teaching hospital, most of the interaction takes place between the patient and the medical students being supervised by the specialist. “He saw me twice,” she states. “He saw me once to take on my case and then he saw me at the end.” One of his residents came down and presented her with a diagnosis of Convergence, which essentially means that the problem is psychological, not physical. As she worked towards being discharged, this diagnosis made less and less sense to her.

Quickly, this led her to anger. Anger first with herself, burning with the suspicion that she may have allowed herself to jeopardize everything she had worked for, to put at risk the future she saw with Sid and the damage she had done to her own body. However, to her, in the hours she had spent in the London hospital, the type of care they were suggesting didn’t seem to fit the diagnosis. Katie noticed that there were no mental health referrals being written. She had also passed the initial test that should have helped to rule out a psychological cause.

One of the staff involved in working towards her discharge was talking about it being a Convergence issue and Katie finally snapped. “I told her to fuck off,” she says, proudly. “If I needed mental health support, someone could have referred me. So they are telling me this is a mental health issue, but no one gave me a referral. So, there is a huge dispute there. If I had that, then why am I not getting referred to a psychiatrist?”

Her refusal to accept the diagnosis drew the attention of the Neurologist who paid her a second visit in order to find out what all the fuss was about. “He heard up the grapevine that I’d told her that, and that a senior resident, who had no bedside manner, [had diagnosed Convergence]. He asked what his senior student had said to me, and he was like ‘No, that’s not right at all’. He said, ‘No, you have a Hemiplegic Migraine. This is what it is, your migraine is doing this to you. This isn’t a Convergence issue.'”

Hemiplegic Migraines are rare enough that many doctors do not have experience treating them. According to the American Migraine Foundation, the symptoms can last anywhere from days to weeks, although the symptoms usually eventually resolve. Katie now found herself in a wheelchair, with limited muscle control on her left side. While she could speak, her words were not clear. Her London doctors decided to send her back to the hospital near her home where she could receive rehab and hopefully be more comfortable.

So Many Hurdles

While Katie had never before allowed her invisible illness to defeat her, this new development of visible symptoms also presented much larger challenges than she had ever faced in the past. What should have been a validation of her years of successfully living with migraines instead turned into a series of obstacles to her recovery.

The first obstacle would be planning the wedding. With only two months left to prepare for a large wedding, Katie would realize that many of the people around her still did not fully grasp what she was going through. “I didn’t want to do it, but it was one of those things, right,” Katie asks rhetorically regarding wedding planning. “Sid has his whole family coming from Europe.”

“It was so overwhelming for me. I had to put on this strong front. And I had to make the choice every day to get out of bed and do all these things. That was the last thing I wanted to do–the making decisions part. I need to walk. I needed to learn how to use my hand again. If I could move my fingers–that’s all I wanted to do. On top of it, I had to plan this wedding. I just wanted someone to make that decision. I wasn’t in the right state of mind to do that. But no one was taking that off my plate.”

In her bed at the hospital, her mind began to call into question her self-identity. She was in the very early stages of coming to grips with the fact that who she was and what she could do might be significantly different from just a few weeks before. These changes, she knew, affected more than just herself. About Sid, she remembers thinking, “’We’re not even married yet, we don’t have that piece of paper and I’m already a burden. This isn’t what he signed up for. He can leave whenever he wants.’ I always had, in the back of my mind, ‘Is he here because he wants to be or because he is obligated?’ His dad died when he was young and, at 17, he was the man of the house. He’s always been– he’s a firefighter –he’s always been there out of duty. But does he want to be? It was hard for me to get over that.” I know now that it is because of love and his commitment to us, but when you’re in that state, it’s hard for your mind not to go to dark places. I married a truly amazing person.”

There was to be no help in conquering this second obstacle. Struggling with these fears and emotions, Katie knew that she wanted help to work through them. However, there were no mental health specialists available to work with her now that she truly needed it. They are accessible after the fact, just not during the trauma and rehab experience. The system isn’t built in a way to provide that sort of responsive care, especially in rural and small-town communities. Her mind and heart heavy with doubt and frustration, Katie turned her attention towards Rehab and did her best to get better, but even here she found obstructions built into the system.

Katie says of the medical staff back in her local hospital, “They had this plan. They would do this meeting about what your plan was –when you would get out– and put it on your board. In my mind I was like, ‘Screw that board, I’m going to get out of here in like, record time! I’ll be in here a week.’ My mom was like, ‘no…’ They came back and my social worker who had my case was like, ‘No, it’s going to be longer.’ Ok, then–two weeks. But it was 5 weeks!” They had put more than a month on her board, but she thought “I’m not going to be here five weeks, no way.”

It didn’t take long for Katie to feel that her plans didn’t seem to mean a whole lot to the medical community.

“In the hospital, they are so policy-driven. They don’t see patients,” she said. They don’t see patient care over policy. Like, it’s a checkmark in policy, ‘ I did it, that’s good, checkmark!. I’m going on to the next patient.” Katie says that, to her, it felt like the emphasis on policy had priority over “‘How can we adapt to fit the patient’s needs?’ Yes, still address what the policy states but, ‘Okay is this still going to fit what the patient needs?'” She says that it felt like once the medical community made a decision, there was no discussion anymore. And yet, it seemed to her that the patient was rarely consulted.

Katie provides the example of showering. Hospital staff required her to demonstrate that she could do it by herself. Even though she had been doing it on her own in London, she had to prove once again what she was capable of. The process, she remembers, felt humiliating. “I had to walk down the hall to another bathroom, to shower in front of someone, just to prove I could do it. For a 26-year-old female, having to shower in front of someone; you just lose everything. I had a shower in my bathroom in my room. We could have done it there in my own setting where I was comfortable. I had a lot of struggles with that. They still could have helped me, and they still could have checked their boxes. I felt like cattle being slaughtered. It was so traumatizing for me.”

The feeling of being a bunch of boxes to be checked off did not end there. “The OT [Occupational Therapist] never came in to look at me and see what my capacity was. There was just a checkmark. Like, ‘Okay, this patient needs to do this’, but [they] never came to see what I could actually do or my ability.” The OT’s interactions with her neighboring patients convinced Katie that, here again, she would need to find the strength to take the lead. “I had a very passive OT who would just come to my room and ask what I wanted to do. And my neighbors, I would hear them, she’d go in and do the same thing, and if they said ‘nothing’ she eventually would just leave. She had no real plan.”

Katie did have an amazing team of physical, speech, and recreational therapists who were willing to adjust their plans to her desire and motivation. Her SLP (Speech-Language Pathologist) helped her to recover some ability to speak, while her PT (Physical Therapist) got her to quickly progress from a wheelchair to a walker, to a cane. She believes she was able to progress so much faster, “because they adapted to my drive, to my determination. And also because I was so young and ready to go with it. I was like, give it to me, I’ll do it. I’d do exercises all the time. I’m like ‘Let’s go!’ As opposed to the OT who was rigid and not able to adapt to a patient as an individual and not a textbook case.”

Katie did spend the full five weeks undergoing Rehabilitation as an inpatient. By the time she was discharged, she had regained her ability to walk, with the help of a cane for stability. Her speech remained slurred, however, as the left facial muscles were not yet fully functional. She required further outpatient rehab for that, and to work on restoring the function of her left arm and hand.

She had been discharged about a month prior to the wedding. But being home had meant that her rehab had been suspended. And there was a waiting list of at least two months for outpatient rehab to start. Ontario has a system of health care that can be delivered in the home, with an overarching government department that coordinates care with individuals. She had to work with the Community Care Access Centre (CCAC), which has just recently been transformed into the Ontario Health teams. “I had to have a meeting with them, and the care worker looked at me and started asking questions like ‘What can you do? Can you clean your house? Do you go upstairs? Do you have a dog?’ She told me, she didn’t know what to do with me. I wasn’t going to be approved for any Rehab in between.

“I came across this CCAC coordinator who looked me up and down,” Katie said. Here was another person who seemed to have a policy and a checklist that Katie just couldn’t get past. “She just put all these obstacles in my way and wouldn’t look up to help me. Two months is the minimum to get me in [back to hospital rehab]. CCAC was supposed to bridge the Rehab gap. I was going four times a week [while an inpatient], so if I could just get in one time a week that would be great. That’s all I wanted. We had insurance to cover Physical Therapy. But it was my hand– my livelihood, everything was on the computer. My hand wasn’t working, I needed Occupational Therapy.”

Through the Dark to Find the Light

With the wedding less than one month away, her central role in its planning and performance loomed large over her. She didn’t feel beautiful. She barely recognized the person that would stare back at her in the mirror. She couldn’t have a conversation with anyone, and she had to put a great amount of energy and concentration into making her facial muscles smile. Even walking was still tiring and difficult.

What should have been a blur of happiness and excitement is instead burned into her memory as cold, discreet milestones that had to be met in order to simply make it through the day. “At the wedding, it was like, ‘Ok, make it to the church.’ From there it was, ‘make it down the aisle.’ Then it was like, ‘make it through pictures, smiling, holding the bouquet,’ because my face would just go wonky. Those little things. I don’t think people realized how hard it was on my wedding day. I didn’t talk to anyone on my wedding day. I left early, I didn’t dance. I danced with Sid and my dad, but that’s all I did.” It took her three days to get out of bed after the wedding due to the physical and emotional exhaustion she experienced.

Katie gives out a quiet sob at the memory and says softly, “I sat in the front lobby. It was awful. I feel bad saying that. All of our loved ones came to experience this special day with us and all I feel is guilt about remembering our day like a dark experience”

The daily struggle to get better and rebuild was made even tougher by a lack of clarity around what the end of it all would look like for her. Would she be able to talk? Would she be able to walk without a cane? Would she be able to rebuild her identity into someone she was comfortable bringing out in public? “I didn’t want people to pity me,” she says. But she couldn’t deny the toll this journey had taken on her mental health, too. “Every morning was my time in the shower, I would give myself 5 minutes. I could cry, I could scream. I could do whatever I wanted. That was my time to feel bad for myself. But after that, ‘That was it, Katie.’ You have to keep going.”

Then the Hemiplegic Migraine nearly won. “There was one day I thought that, ‘Hey we’re going to end. This is it. I’m going to do it. I’m done. Katie is going away forever.’ And that was it. Because there’s no mental health support. There’s no counseling, there’s nothing. I asked, and they would not give it.” This was her lowest point, the lowest she had ever felt in her life. However, her story did not end there on that day. Somehow, she managed to keep going.

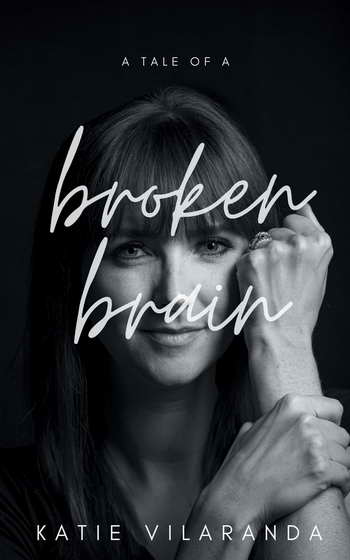

Her marriage to Sid survived and is strong. They have a son now, a happy little guy. With rehab it still took her a year to “get back”, to feel comfortable seeing people. She has written a book about her journey, that will be released in the coming months, which has helped her deal with the hardest year of her life. She has gotten back into charity and volunteer work as well. However, the acknowledgment is there that Katie is not the same person as before the Hemiplegic Migraine struck.

Movement and use of her left side slowly came back to the point where she could function again, and she eventually felt well enough to reopen her business. Some of her clients came back, and she would eventually find new ones. She still isn’t 100 percent though. Physical deficits remain, along with a brace for her left wrist, and there are days when she has to lie low. Now her clients have to know upfront that there may be days she won’t be available. She has created contingency plans for the bad days and has become more selective, taking clients that she feels understand her; ones she fits with. All are constant reminders of how quickly things changed.

Katie is adamant that people not feel sorry for her. She has come to realize that while things are different, she still has just as much to offer her loved ones and clients as she did before the changes. She tells her story because she knows the feelings of isolation and fear that people who experience health problems can often feel as they struggle to come to grips with the changes they will have to live with for the rest of their lives. For many, mental health challenges come part and parcel with physical ailments. These challenges are often overlooked by a system not designed to address them, while the people closest to a patient are not equipped to understand them.

Mostly, Katie wants people to know that they are not alone. Your struggle is probably different than hers, but there are points of commonality. There will be dark days. There will be depression. It will be hard to find help. She wants people to know that if you end up in the healthcare system, you need to be prepared to advocate for yourself, to fight the system when you have to. It will be hard, because you should be spending your energy getting well, but if you don’t push back you will find yourself excluded from decisions about your own care. But mostly she wants you to know that she made it through, even with all the obstacles put in place by those who should be, or think they are, helping.

Make it to the church. Make it down the aisle. Make it out of bed. Make it out of the shower. You can do it. You are not alone.

You can read the whole story in Katie’s book, available at amazon.ca

Please support Candid Badger! Help us continue to bring a variety of stories, local and distant, to the community.

Learn more about Katie at katievillaranda.com

Feature Image from Pexels.com / Katie’s Photos courtesy of Katie Villarana

What an amazing story of resilience and spirit! The lack of access to mental health care is concerning, as this would’ve been beneficial in providing another solid layer of support in her recovery. Katie shows us the significance of perseverance and self-advocacy in overcoming life’s obstacles. Thank you for sharing!

Beautiful, Katie. I’m proud of you. Love you ?